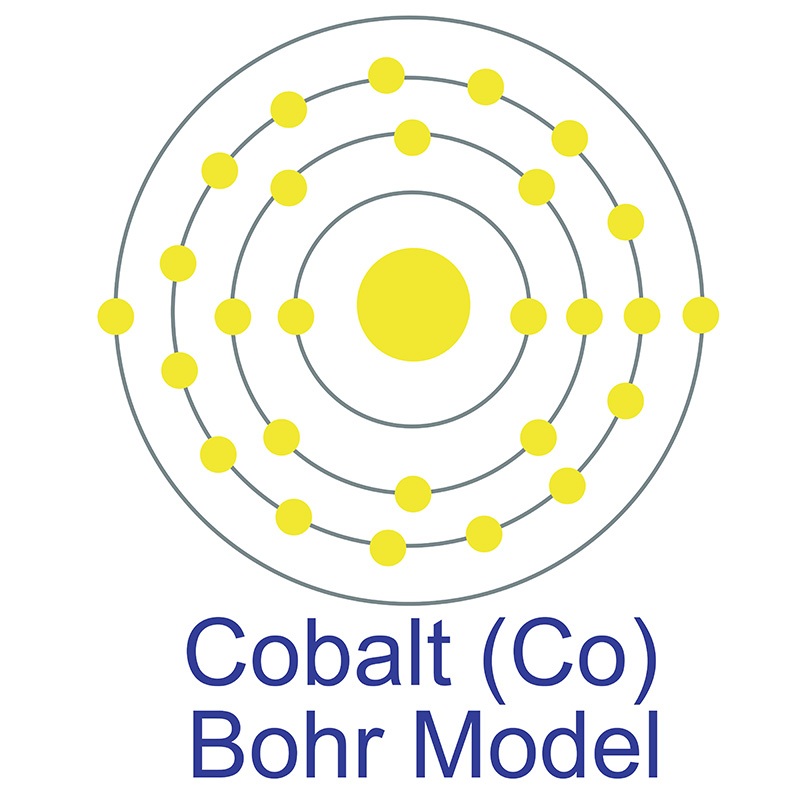

See more Cobalt products. Cobalt (atomic symbol: Co, atomic number: 27) is a Block D, Group 9, Period 4 element with an atomic weight of 58.933195.  The number of electrons in each of cobalt's shells is 2, 8, 15, 2 and its electron configuration is [Ar]3d7 4s2. The cobalt atom has a radius of 125 pm and a Van der Waals radius of 192 pm. Cobalt was first discovered by George Brandt in 1732. In its elemental form, cobalt has a lustrous gray appearance. Cobalt is found in cobaltite, erythrite, glaucodot and skutterudite ores.

The number of electrons in each of cobalt's shells is 2, 8, 15, 2 and its electron configuration is [Ar]3d7 4s2. The cobalt atom has a radius of 125 pm and a Van der Waals radius of 192 pm. Cobalt was first discovered by George Brandt in 1732. In its elemental form, cobalt has a lustrous gray appearance. Cobalt is found in cobaltite, erythrite, glaucodot and skutterudite ores.  Cobalt produces brilliant blue pigments which have been used since ancient times to color paint and glass. Cobalt is a ferromagnetic metal and is used primarily in the production of magnetic and high-strength superalloys. Co-60, a commercially important radioisotope, is useful as a radioactive tracer and gamma ray source. The origin of the word Cobalt comes from the German word "Kobalt" or "Kobold," which translates as "goblin," "elf" or "evil spirit.

Cobalt produces brilliant blue pigments which have been used since ancient times to color paint and glass. Cobalt is a ferromagnetic metal and is used primarily in the production of magnetic and high-strength superalloys. Co-60, a commercially important radioisotope, is useful as a radioactive tracer and gamma ray source. The origin of the word Cobalt comes from the German word "Kobalt" or "Kobold," which translates as "goblin," "elf" or "evil spirit.

Materials

Materials by Form

2D Materials Alloy & Alloy Forms Pure Metals & Metal FormsCeramic FibersFoams: Metallic & Ceramic High Purity Materials Isotopes MXenesOxides Rare Earths Semiconductors Solutions

Chemicals & Salts

All Chemicals & Salts Acetates Aluminides Ammonium Sulfates Antimonides Arsenates Benzoate Bromates Bromides Carbonates Chlorides Chromates Fluorides Hydrides Hydroxides Iodates Iodides Lactates Molybdates Nitrates Oxalates Oxides Perchlorates Phosphates Selenates Selenides Selenites Silicates Stearates Sulfates Sulfides Sulfites Tantalates Tellurates Tellurides Tellurites ThiocyanatesVanadates

Ceramics

Nanomaterials

Organometallics

Materials by Application

Additive Manufacturing & 3D Printing Battery & Supercapacitor Materials Catalysts Dental Materials Electronics Materials Fuel Cell Materials Fusion EnergyGlass Manufacturing Green Technology & Alternative Energy Hydrogen Storage Laser Crystals Life Sciences & Biomaterials Metallurgy Nanotechnology & Nanomaterials Optical Materials Photovoltaic & Solar Energy Plating Pigments & Coatings Research & Development Space Technology Sputtering Targets Thin Film Deposition Water Treatment Weather Modification

Life Science Chemicals

Life Science Products AlcoholsAldehydesAmidesAminesAmino Acids & DerivativesAromaticsArylsAzetidinesBenzimidazolesBenzisoxazolesBenzodioxansBenzofuransBenzothiazolesBenzothiophenesBenzoxazolesCarboxylic AcidsEnzymes & InhibitorsEstersEthersFluorinated Building BlocksFuransHalidesImidazolesImidazolidinesIndazolesIndolesIndolinesIsoquinolinesIsoxazolesKetonesMorpholinesNaphthyridinesNitrilesOrganoboronOrganosiliconOxadiazolesOxazolesPharmaceuticals & IntermediatesPhenolsPhytochemicalsPiperazinesPiperidinesPyrazinesPyrazolesPyridazinesPyridinesPyrimidinesPyrrolesPyrrolidinesPyrrolinesQuinazolinesQuinolinesQuinoxalinesSpiroesSulfonyl ChloridesTetrahydroisoquinolinesTetrahydropyransTetrahydroquinolinesTetrazolesThiadiazolesThiazolesThiazolidinesThiolsThiophenesTriazinesTriazoles

About Us

Locations

Austria Belgium Brazil Canada China & Hong Kong Czech Republic Denmark Finland France Germany Greece Hungary India Indonesia Israel Italy Japan Malaysia Mexico Netherlands Norway Philippines Poland Portugal Russia Singapore South Korea Spain Sweden Switzerland Taiwan Thailand Turkey United Kingdom United States

Industries

Aerospace Agriculture Automotive Chemical Manufacturing Defense Dentistry Electronics Energy Storage & Batteries Fine Art Materials Fuel CellsFusion Energy Glass Investment Grade Metals Jewelry & Fashion Lasers Lighting Medical Devices Museums & Galleries Nuclear Energy Oil & Gas Optics Paper & Pulp Pharmaceuticals & Cosmetics Research & Laboratory Robotics Solar Energy Space Sports Equipment Steel & Alloy Producers Textiles & Fabrics Water Treatment Municipalities

Follow Us

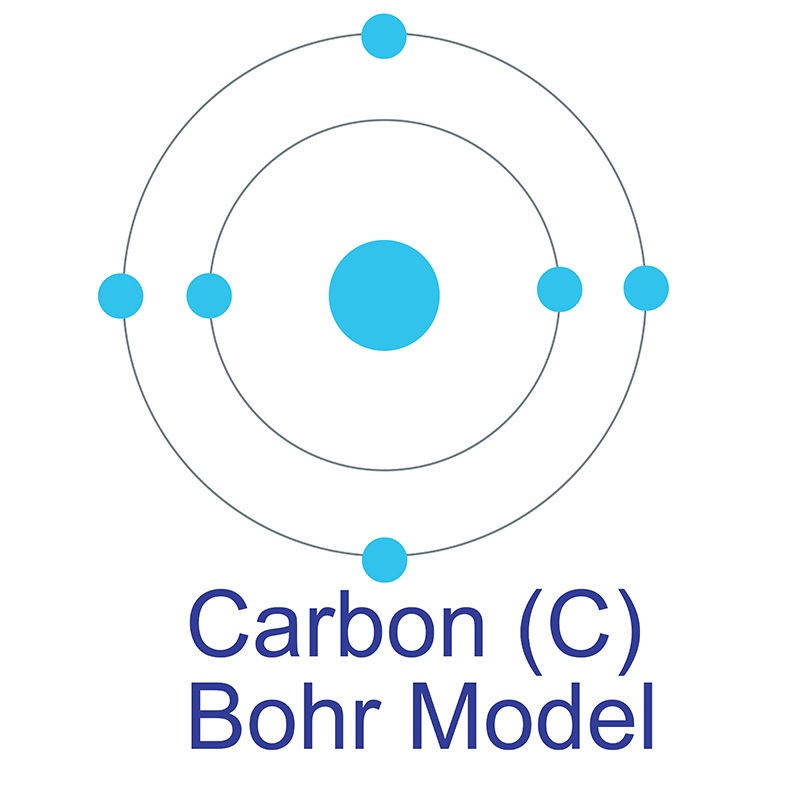

The number of electrons in each of Carbon's shells is 2, 4 and its electron configuration is [He]2s2 2p2. In its elemental form, carbon can take various physical forms (known as allotropes) based on the type of bonds between carbon atoms; the most well known allotropes are diamond, graphite, amorphous carbon, glassy carbon, and nanostructured forms such as carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, and nanofibers . Carbon is at the same time one of the softest (as graphite) and hardest (as diamond) materials found in nature. It is the 15th most abundant element in the Earth's crust, and the fourth most abundant element (by mass) in the universe after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon was discovered by the Egyptians and Sumerians circa 3750 BC. It was first recognized as an element by Antoine Lavoisier in 1789.

The number of electrons in each of Carbon's shells is 2, 4 and its electron configuration is [He]2s2 2p2. In its elemental form, carbon can take various physical forms (known as allotropes) based on the type of bonds between carbon atoms; the most well known allotropes are diamond, graphite, amorphous carbon, glassy carbon, and nanostructured forms such as carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, and nanofibers . Carbon is at the same time one of the softest (as graphite) and hardest (as diamond) materials found in nature. It is the 15th most abundant element in the Earth's crust, and the fourth most abundant element (by mass) in the universe after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon was discovered by the Egyptians and Sumerians circa 3750 BC. It was first recognized as an element by Antoine Lavoisier in 1789.