About Mercury

Mercury is the only metal that is liquid at standard temperature and pressure, a property that results from a unique electron configuration that gives rise to unusually weak metallic bonds. Its chemical symbol Hg arises from the latin hydragyrum, meaning “liquid-silver”, and its common name was borrowed from the Roman god Mercury. The element was known to ancient civilizations, and though its metallic nature was not initially understood, its unique properties led it to be almost invariably seen as special or even imbued with magical powers. Its earliest uses were ceremonial, decorative, or medical; it was used in medical ointments and elixirs, cosmetics, and reflecting pools, and frequently was buried in large quantities alongside dead rulers. Medical uses of mercury are so embedded in some traditional healing practices that some practitioners still recommend the consumption of the mercury ore cinnabar for specific ailments or as a supplement for general health.

It has long been recognized that acute inhalations of mercury can lead to significant symptoms, but it is now understood that the slow elimination of most forms of mercury from the body ensures that even low levels can cause severe damage if chronic exposure allows for significant accumulation. A famous example of such gradual poisonings resulted from the use of mercuric nitrate in processing the animal skins used in 18th and 19th century hatmaking, which led to the coining of the phrase “mad as a hatter.” Increasing recognition of the dangers of chronic mercury exposure and of widespread environmental contamination due to mercury-containing products has driven significant reduction in many classical uses of the element.

Perhaps the most longstanding use of mercury not based primarily on its alluring physical properties was in amalgamation. Mercury will form amalgams with most common metals with the notable exception of iron; as early as 500 BCE this was exploited for extraction or refining of silver and gold. This practice continued in precious metal mining for centuries, though it’s use dwindled with increasing recognition of mercury’s toxicity until ceasing altogether in modern times. Amalgams were also widely used in dental fillings, and are still sometimes used this way today, though both toxicity and cosmetic concerns have led to their increasing replacement by alternative materials.

The pattern of widespread exploitation of unique properties followed by drastic scalebacks or total cessation of use in a given application due to greater recognition of safety risks has repeated throughout mercury’s history. Liquid mercury is opaque, dense, and displays almost-linear thermal expansion, making it ideal for use in instruments for measuring temperature or pressure. It is still used this way in some industrial and technical applications, but has been largely removed from medical equipment and most consumer versions of such products. Additionally, as a liquid that conducts electricity, it was used in mercury switches, which were often used in home light switches and thermostats, but these uses were discontinued. Mercury was also a common component of some types of batteries, but concerns about contaminations of landfills have all but eliminated this use. Mercury sulfide, which occurs naturally as the mineral cinnabar, has been used to produce brilliant warm-colored pigments, most famously “China red”, for centuries and is still used by some artists, but has been replaced by less-toxic pigments for most uses.

Even mercury’s toxicity has been exploited for practical applications. Mercury has been used in insecticides, herbicides, wood preservatives, and anti-fouling paints, but widespread use of all of these products have been discontinued. The organomercury preservative thiomersal was once used widely in vaccines, and though unlike most mercury compounds it produced a metabolite--ethylmercury--that was known to be eliminated from the body relatively quickly and therefore be nontoxic at the extremely low concentrations used in vaccines, public concern about the potential for toxicity has led to its elimination from most formulations. Mercury has also been used as an antiseptic and a diuretic, but these uses are now exceedingly rare and continue to decline.

Reductions in mercury usage in industrial applications have proceeded somewhat more slowly than the elimination of mercury from consumer products. Traditional chloralkali plants use mercury as one electrode in the electrolysis of sodium chloride to produce sodium hydroxide and chlorine gas. New chloralkali plants are required to be designed for use of alternative technology that does not require mercury, but existing plants still consume the majority of mercury produced. Mercury also continues to be used in a number of niche laboratory applications, including liquid mirror telescopes, and in the production of a few compound semiconductor materials used for infrared detection.

A notable exception to the elimination of mercury from consumer products is seen in the proliferation of fluorescent light bulbs which contain small amounts of mercury vapor. The energy efficiency of fluorescent bulbs compared to traditional incandescent lighting is generally considered to be an advantage large enough to outweigh the risks associated with the small amount of mercury the bulbs contain, however such bulbs do require careful disposal, and other energy efficient lighting technologies such as LEDs are beginning to be a competitive alternative for at least some lighting applications.

Mercury occurs naturally in elemental form on occasion, but is mostly found as the sulfide mineral cinnabar. It is extracted from this mineral by roasting to produce mercury vapor and sulfur dioxide. Mercury is also sometimes recovered as a byproduct of silver and gold mining, and recycling of old mercury-containing devices is a significant source of the metal.

Mercury is used in the manufacture of industrial chemicals and in electronic applications. For example, mercury is used as gaseous mercury in fluorescent lamps. Some thermometers, particularly those which are used to measure high temperatures, still use mercury. Many of the applications that mercury has been used for in the past are slowly being phased out due to health and safety regulations. Mercury is available as metal and compounds with purities from 99% to 99.999% (ACS grade to ultra-high purity). Mercury is available in elemental or metallic form as mercury liquid. Mercury oxides are available for such uses as optical coating and thin film applications. Oxides tend to be insoluble. Mercury is also available in soluble forms including chlorides and nitrates. These compounds can be manufactured as solutions at specified stoichiometries.

Mercury is used in the manufacture of industrial chemicals and in electronic applications. For example, mercury is used as gaseous mercury in fluorescent lamps. Some thermometers, particularly those which are used to measure high temperatures, still use mercury. Many of the applications that mercury has been used for in the past are slowly being phased out due to health and safety regulations. Mercury is available as metal and compounds with purities from 99% to 99.999% (ACS grade to ultra-high purity). Mercury is available in elemental or metallic form as mercury liquid. Mercury oxides are available for such uses as optical coating and thin film applications. Oxides tend to be insoluble. Mercury is also available in soluble forms including chlorides and nitrates. These compounds can be manufactured as solutions at specified stoichiometries.

Mercury Properties

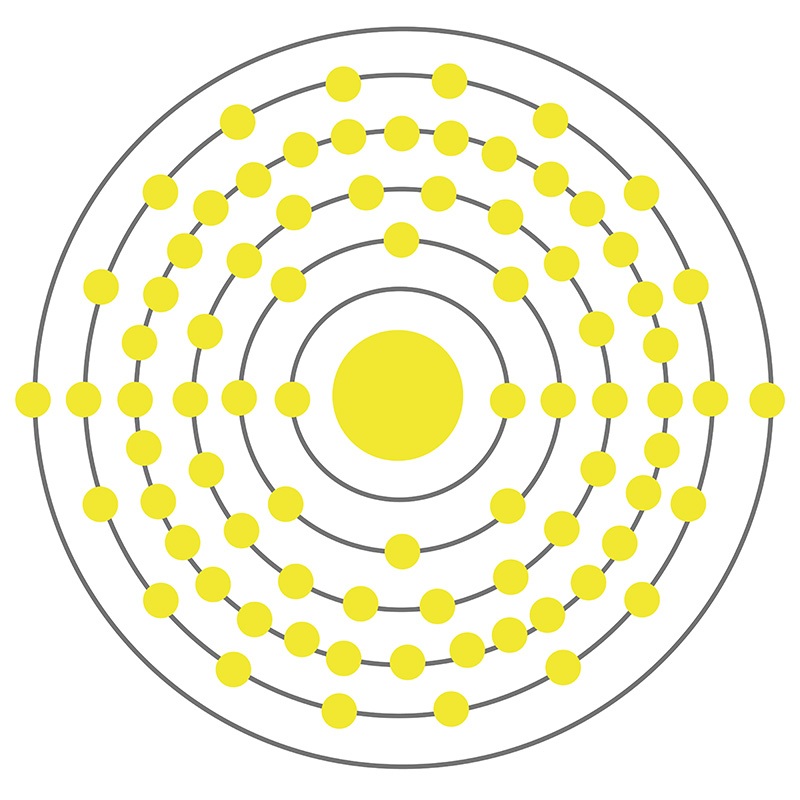

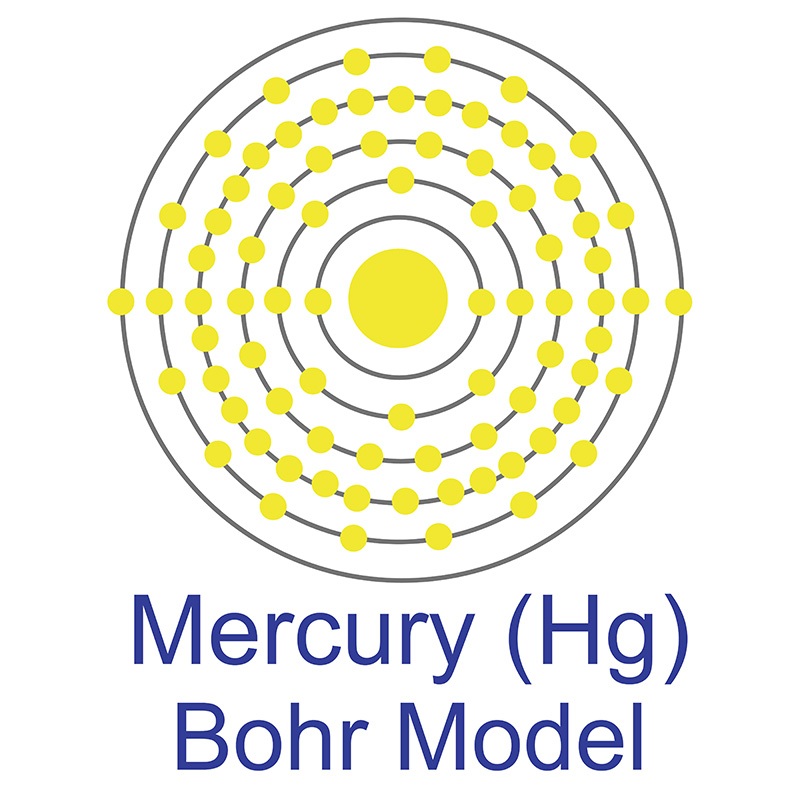

Mercury is a Block D, Group 12, Period 6 element. The number of electrons in each of Mercury's shells is 2, 8, 18,32, 18, 2 and its electronic configuration is [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2. The mercury atom has a radius of 216.pm and its Van der Waals radius is 155.pm. In its elemental form, CAS 7439-97-6, mercury has a silvery appearance. Mercury is found both as a native metal and in cinnabar, corderoite, and livingstonite ores. Mercury was named after the planet "Mercury" and has been known since ancient times.

Mercury is a Block D, Group 12, Period 6 element. The number of electrons in each of Mercury's shells is 2, 8, 18,32, 18, 2 and its electronic configuration is [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2. The mercury atom has a radius of 216.pm and its Van der Waals radius is 155.pm. In its elemental form, CAS 7439-97-6, mercury has a silvery appearance. Mercury is found both as a native metal and in cinnabar, corderoite, and livingstonite ores. Mercury was named after the planet "Mercury" and has been known since ancient times.

Health, Safety & Transportation Information for Mercury

Mercury is very toxic. Safety data for Mercury and its compounds can vary widely depending on the form. For potential hazard information, toxicity, and road, sea and air transportation limitations, such as DOT Hazard Class, DOT Number, EU Number, NFPA Health rating and RTECS Class, please see the specific material or compound referenced in the Products tab. The below information applies to elemental (metallic) Mercury.

| Safety Data | |

|---|---|

| Material Safety Data Sheet | MSDS |

| Signal Word | Danger |

| Hazard Statements | H330-H360D-H372-H410 |

| Hazard Codes | T+,N |

| Risk Codes | 61-26-48/23-50/53 |

| Safety Precautions | 53-45-60-61 |

| RTECS Number | OV4550000 |

| Transport Information | UN 2809 8/PG 3 |

| WGK Germany | 3 |

| Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling (GHS) |

|

Mercury Isotopes

Mercury has seven stable isotopes:

| Nuclide | Isotopic Mass | Half-Life | Mode of Decay | Nuclear Spin | Magnetic Moment | Binding Energy (MeV) | Natural Abundance (% by atom) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 171Hg | 171.00376(32)# | 80(30) µs [59(+36-16) µs] | Unknown | 3/2-# | N/A | 1291.69 | - |

| 172Hg | 171.99883(22) | 420(240) µs [0.25(+35-9) ms] | Unknown | 0 | N/A | 1309.09 | - |

| 173Hg | 172.99724(22)# | 1.1(4) ms [0.6(+5-2) ms] | Unknown | 3/2-# | N/A | 1317.17 | - |

| 174Hg | 173.992864(21) | 2.0(4) ms [2.1(+18-7) ms] | Unknown | 0+ | N/A | 1325.25 | - |

| 175Hg | 174.99142(11) | 10.8(4) ms | a to 171Pt | 5/2-# | N/A | 1333.33 | - |

| 176Hg | 175.987355(15) | 20.4(15) ms | a to 172Pt; ß+ to 176Au | 0+ | N/A | 1350.72 | - |

| 177Hg | 176.98628(8) | 127.3(18) ms | a to 173Pt; ß+ to 177Au | 5/2-# | N/A | 1358.8 | - |

| 178Hg | 177.982483(14) | 0.269(3) s | a to 174Pt; ß+ to 178Au | 0+ | N/A | 1366.88 | - |

| 179Hg | 178.981834(29) | 1.09(4) s | a to 175Pt; ß+ to 179Au; ß+ + p to 178Pt | 5/2-# | N/A | 1374.96 | - |

| 180Hg | 179.978266(15) | 2.58(1) s | ß+ to 180Au; a to 176Pt; SF | 0+ | N/A | 1392.35 | - |

| 181Hg | 180.977819(17) | 3.6(1) s | ß+ to 181Au; a to 177Pt; ß+ + p to 180Pt; ß+ + a to 177Ir | 1/2(-) | N/A | 1400.43 | - |

| 182Hg | 181.97469(1) | 10.83(6) s | ß+ to 182Au; a to 178Pt; ß+ + p to 181Pt | 0+ | N/A | 1408.51 | - |

| 183Hg | 182.974450(9) | 9.4(7) s | ß+ to 183Au; a to 179Pt; ß+ + p to 182Pt | 1/2- | N/A | 1416.59 | - |

| 184Hg | 183.971713(11) | 30.6(3) s | ß+ to 184Au; a to 180Pt | 0+ | N/A | 1424.67 | - |

| 185Hg | 184.971899(17) | 49.1(10) s | ß+ to 185Au; a to 181Pt | 1/2- | N/A | 1432.74 | - |

| 186Hg | 185.969362(12) | 1.38(6) min | ß+ to 186Au; a to 182Pt | 0+ | N/A | 1450.14 | - |

| 187Hg | 186.969814(15) | 1.9(3) min | ß+ to 187Au; a to 183Pt | 3/2- | N/A | 1458.22 | - |

| 188Hg | 187.967577(12) | 3.25(15) min | ß+ to 188Au; a to 184Pt | 0+ | N/A | 1466.3 | - |

| 189Hg | 188.96819(4) | 7.6(1) min | ß+ to 189Au; a to 185Pt | 3/2- | N/A | 1474.38 | - |

| 190Hg | 189.966322(17) | 20.0(5) min | ß+ to 190Au; a to 186Pt | 0+ | N/A | 1482.45 | - |

| 191Hg | 190.967157(24) | 49(10) min | ß+ to 191Au | 3/2(-) | N/A | 1490.53 | - |

| 192Hg | 191.965634(17) | 4.85(20) h | EC to 192Au; a to 188Pt | 0+ | N/A | 1498.61 | - |

| 193Hg | 192.966665(17) | 3.80(15) h | ß+ to 193Au | 3/2- | N/A | 1506.69 | - |

| 194Hg | 193.965439(13) | 444(77) y | EC to 194Au | 0+ | N/A | 1514.77 | - |

| 195Hg | 194.966720(25) | 10.53(3) h | EC to 195Au | 1/2- | 0.541475 | 1522.85 | - |

| 196Hg | 195.965833(3) | Observationally Stable | - | 0+ | N/A | 1530.93 | 0.15 |

| 197Hg | 196.967213(3) | 64.14(5) h | EC to 197Au | 1/2- | 0.527374 | 1539.01 | - |

| 198Hg | 197.9667690(4) | Observationally Stable | - | 0+ | N/A | 1547.08 | 9.97 |

| 199Hg | 198.9682799(4) | Observationally Stable | - | 1/2- | 0.5058852 | 1555.16 | 16.87 |

| 200Hg | 199.9683260(4) | Observationally Stable | - | 0+ | N/A | 1563.24 | 23.1 |

| 201Hg | 200.9703023(6) | Observationally Stable | - | 3/2- | -0.560225 | 1562 | 13.18 |

| 202Hg | 201.9706430(6) | Observationally Stable | - | 0+ | N/A | 1570.08 | 29.86 |

| 203Hg | 202.9728725(18) | 46.595(6) d | ß- to 203Tl | 5/2- | 0.8489 | 1578.16 | - |

| 204Hg | 203.9734939(4) | Observationally Stable | - | 0+ | N/A | 1586.24 | 6.87 |

| 205Hg | 204.976073(4) | 5.14(9) min | ß- to 205Tl | 1/2- | N/A | 1594.32 | - |

| 206Hg | 205.977514(22) | 8.15(10) min | ß- to 206Tl | 0+ | N/A | 1602.4 | - |

| 207Hg | 206.98259(16) | 2.9(2) min | ß- to 207Tl | (9/2+) | N/A | 1601.16 | - |

| 208Hg | 207.98594(32)# | 42(5) min [41(+5-4) min] | ß- to 208Tl | 0+ | N/A | 1609.24 | - |

| 209Hg | 208.99104(21)# | 37(8) s | Unknown | 9/2+# | N/A | 1608 | - |

| 210Hg | 209.99451(32)# | 10# min [>300 ns] | Unknown | 0+ | N/A | 1616.08 | - |